FUTURES: Removing Plastics From Our Oceans – The dangers of uncertain solutions to a looming ecological crises

by A’liya Spinner

新时代渔业

New Age Fishing

Abebi Kanumba靠在“鹈鹕号”不断晃动的船壁上,咸味的裹挟着热浪的海水溅上甲板,洒到了她的脸上。她忍住了想要揉一揉眼睛的冲动,双手紧紧地握着一根长竿,它悬在渔船的船舷上,摇摇欲坠,在它的尽头悬挂着一张编织得很细致的网,从大西洋的水面上掠过。浮光跃金,海面上跳跃的晨光诱惑着她用她的网去捕捉它们。但她尽力保持着长杆静止平衡,忍着她眼睛和前臂的酸痛的感觉。黑线鳕和鳕鱼不是鹈鹕号今天要打捞的东西,她必须时刻警醒。

The salty sea spray burns Abebi Kanumba’s exposed face as she leans over the edge of the rocking Pelican. She resists the urge to wipe her eyes, keeping her hands locked around a long pole that’s been precariously balanced on the gunwale of the fishing vessel, a finely-woven net dangling from its end and over the rippling surface of the Atlantic Ocean. The light of late morning dances on the water, imitating the flash of fish scales just beneath the churning waves and tempting her to scoop at fleeting shadows with her net. But she holds still and poised, ignoring the pain in her eyes and ache in her forearms. Haddock and cod are not what the Pelican has come fishing for today, and she must be ready at all times.

“快点儿,有动静了!”Imamu船长的声音盖过了船引擎的轰鸣和水飞溅的声音。她抬头一看,只见他站在门框旁,黝黑的皮肤上闪烁着汗水的光芒,这是他早上辛辛苦苦地上下拖网的结果。每次看到大网涨空,无论Abebi在鹈鹕号上服务多久,都会感到毛骨悚然。她永远也无法接受曾经富饶的非洲海岸已经变的空旷无比的事实。

“Look sharp, I see movement!” Comes the voice of Captain Imamu over the roar of the boat’s engines and the spray of water. She glances up, seeing him standing beside the gantry, sweat glistening on his dark skin from a morning of hard labor raising and lowering the boat’s trawl. Each time the large net has risen empty, an eerie sight no matter how long Abebi serves aboard the Pelican. She will never get accustomed to the empty swaths of ocean surrounding the once abundant coast of Africa.

“他们在那!”另一名船员在船头喊着,指着右舷。“鹈鹕”号开始靠近一大片漂浮的灰白色物质。那是一堆的缠绕在一起的塑料垃圾网,在“鹈鹕”号行驶时激起的波浪中起伏。

“There they are!” Another crew member shouts from the bow, pointing over the starboard side as the Pelican draws into range of a floating mass of pale detritus. The loosely-connected mesh of plastic waste bobs on the waves they stir up on approach.

“难怪海洋变得安静了,”Nkechi——倚靠在Abebi旁边的长杆上的渔民——在他们靠近缠结在一起的塑料袋、瓶子和叫不出名字的东西组成的漂浮物时说,“这是大西洋垃圾带的一部分。”

“No wonder the ocean has gone quiet,” Nkechi— a fisherman leaning on a second long pole beside Abebi— says as they near the tangled raft of plastic bags, bottles, and formless debris. “It’s a piece of the Atlantic garbage patch.”

“那是垃圾病。”Imamu船长纠正道:“一种比寄生虫更可怕的东西——正在非洲肆虐。”

“The garbage blight,” Captain Imamu corrects. “It’s no better than a parasite, gorging itself on Africa.”

“而且它带来的后果更糟,”Nkechi吐了一口唾沫。Abebi同意他的意见,但她什么也没说,只是继续用目光扫过海面。Imamu和Nkechi也在观望,后者拿着鱼网,而前者则拿着一支矛枪,举在波光粼粼的海面上,随时准备发动攻击。Abebi知道Senegalian船长的拖网渔船的历史,早在联合国要求西非船只放弃寻找黑线鳕和更难以寻找的猎物前就已经存在了——而现在,一个这样的猎物正出现在Abebi的眼前,朝着Imamu船长绑在船底用作诱饵的塑料冲去。

“And what it brings with it is even worse,” Nkechi spits. Abebi agrees with her crewmate, but she says nothing, scanning the water with practiced eyes. Imamu and Nkechi watch too, the latter with his pole-net, and the former with a speargun that he holds over the sparkling sea, poised to strike. Abebi knows that the Senegalian captain has a history with trawlers that long predates the United Nations’ demand that West African boats abandon their hunt for haddock and look for more elusive prey— a prey that Abebi now spots, darting towards the lines of plastic dross that Captain Imamu ties to the bottom of the ship as bait.

Abebi熟练地挥舞扭转着她的长杆,把网浸入水中,然后一气呵成地把网捞出来。Nkechi也做了同样的事,但他的网中空无一物,而她的网中的猎物正在不断扭动着。她做了个鬼脸,把杆子往后一滑,然后熟练地把杆子的一端使劲往下推;那个困在网中的苍白的生物就从空中飞了过去,砰的一声落在甲板上。

With a practiced swing, Abebi twists her long pole, dipping the net into the water and scooping it back out in a single motion. Nkechi does the same, but his net rises empty, while hers thrashes and writhes. With a grimace of effort, she slides her pole back and then shoves down hard on its end in a motion that she’s long perfected; the pale creature tangled in the mesh flies through the air and lands on the deck with a hollow thud.

“这是我见过的最大的一只!”Nkechi惊叹地说道。

“That’s the biggest one I’ve ever seen,” Nkechi comments in awe.

“它们越来越大了,”Imamu船长回答说,他把靴子踩在这只扭动着的动物的尾巴上,用他的矛枪把它刺穿。“这意味着我们可以更轻松地捕捉它们。”他俯下身来,抓住它们捕捉到的鱼的鱼鳃,把它举起来,向船员们展示了一会儿,让他们欣赏。Abebi感到一阵恶心,毛骨悚然;这条“鱼”很长,但是苍白、畸形,长着可怕的嚼塑料的牙齿和凸出的眼睛。Nkechi是对的,它比她以前捕获的任何鱼都要大。

“They’re getting bigger,” Captain Imamu replies, putting his boot down on the writhing animal’s tail and skewering it with his speargun. “All it means is easier hunting for us.” He reaches down and lifts their catch by its gills, showing it off to the crew for a moment for them to admire. Abebi feels a tingle of disgust go down her spine; the “fish” is long, pale, and deformed, with terrible, plastic-chewing teeth and bulging eyes. And Nkechi is right— it’s bigger than any she’s ever caught before.

在观察了一会儿这个巨大的海洋生物之后,Imamu船长把它扔进了一个大箱子里,那里放着稍早前打捞到的一些较小的生物。然后他转过身去,回头望着船舷,看着船上那些苍白的鳝鱼似的东西开始聚拢在一起。他们的现代拖网对捕捉这种滑溜溜的鱼毫无用处,这些鱼不是成群结队地在公海上游来游去,而是在像前面这条鱼一样的垃圾附近的水面上聚集起来的。有传言说,中国和美国一些富有的公司正在投入数百万美元开发新的大型机器,他们承诺,这些机器可以在一天内消灭成千上万这样的怪物——塞内加尔渴望看到这个大胆的承诺实现,但这种机器会否免费提供给他们依然不能确定。然而这些这对Abebi来说并不重要;在他们神奇的机器完成之前,那些国力更强的国家在保护他们的海岸时,也只能使用与其他国家相同的工具:竿子、渔网和鱼叉。地球上所有的国家在对付这种奇怪的、新出现的瘟疫时都显得无能为力。

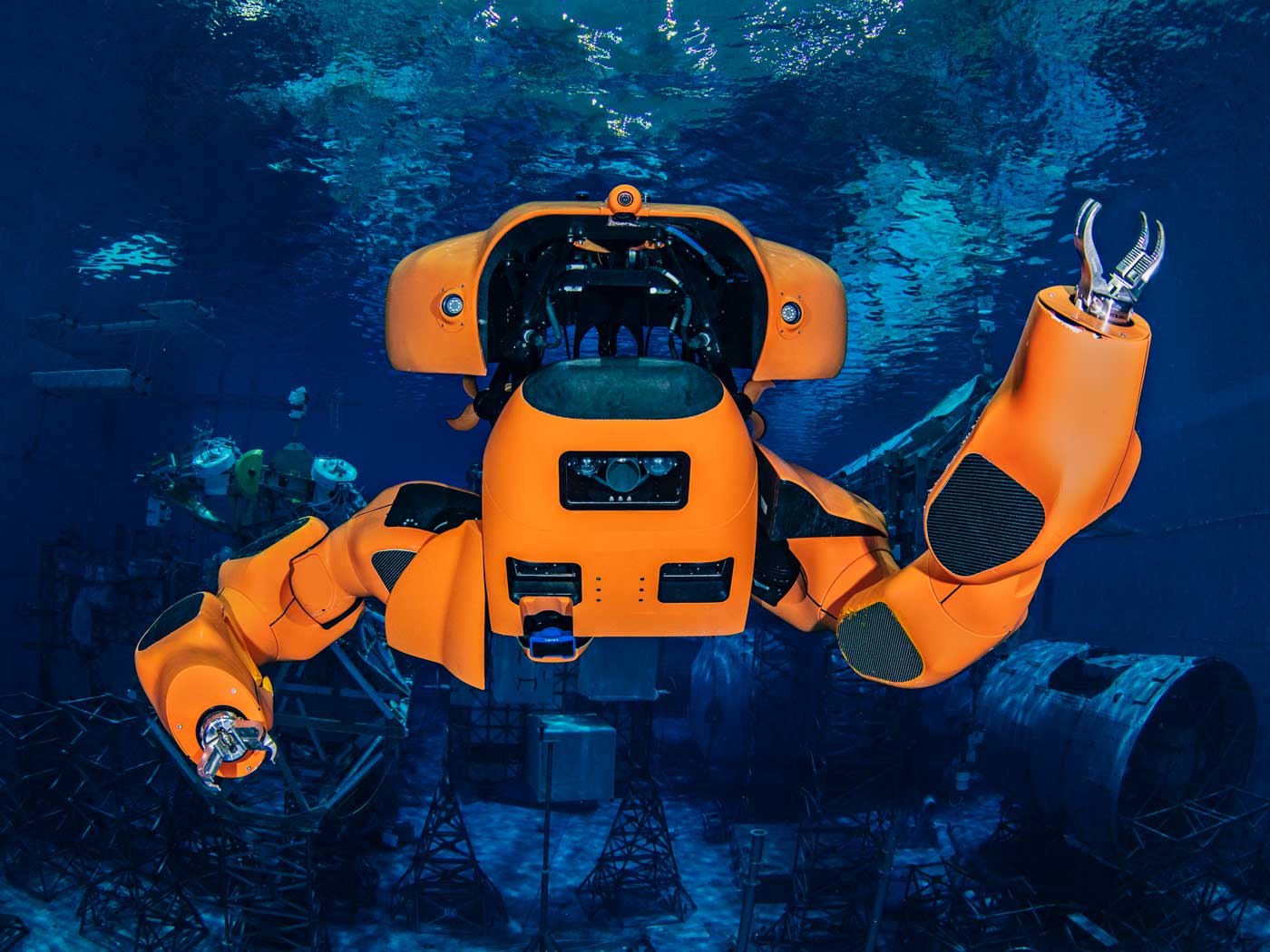

After a moment of observing the monstrous sea creature, Captain Imamu tosses it into a large bin, where it joins a few smaller specimens from earlier that morning. Then he turns away, looking back over the gunwale, at the pale, eel-like shapes beginning to coalesce on the boat. Their modern trawl was useless for catching the slippery fish, which didn’t travel in schools through the open ocean but rather congealed at the surface near garbage patches like the one ahead of them. Rumor had it that wealthy Chinese and American corporations were pouring millions into developing huge machines that could, they promised, destroy the monsters by the thousands in a day— a bold promise that Senegal was eager to see but skeptical about ever being given for free. Not that it mattered much to Abebi; until the completion of their wondrous machines, countries that were used to being the first in everything were limited to the same solutions as the rest of the world when it came to protecting their coasts: poles, nets, and harpoons. All of the nations of Earth had found themselves equally inadequate at fighting this strange, new-age plague.

“回去工作,”Imamu船长命令道。“联合国会按捕捉到的数量支付的。”他用矛枪的末端轻敲甲板。“有人会把海里的垃圾拖走的。也许当它们挨饿时,就会离开这片水域。”

“Back to work,” Captain Imamu orders. “The United Nations pays by the head.” He taps the deck with the end of his speargun. “And someone haul in that garbage mass. Maybe they’ll leave these waters once they start starving.”

阿比照她被要求的那样做了,她把注意力转回到海上,准备网捕另一条这样的鱼,或是大佬起另一堆塑料。她同意船长的观点——如果海中漂浮的塑料被拖到陆地上,吃塑料的鱼就会离开——但她也知道,海洋中的塑料比他们从表面清理出来的要多。一旦吞噬垃圾的瘟疫扩散到这里,那么这些吃垃圾的鱼就几乎不可能被赶走了。它们暴食所产生的化学物质(由基因突变导致的胃酶改变产生)会杀死海中所有像Imamu船长这样的渔民赖以生存的鱼,迫使他们向联合国寻求生计,拿着微薄的薪水去处理富裕国家创造的怪物——这些国家大都鄙夷贫穷的非洲国家,直到他们需要非洲人来处理他们创造的怪物。

Abebi does as she’s told, turning back to the water and preparing her net to snag either another fish or the edge of the loosely-connected raft. She appreciates the sentiment— that the plastic eaters would leave if the floating islands were taken back to land for proper disposal— but she knows that the plastic in the ocean is more abundant than they could ever clean from the surface. Once the plague of garbage-eaters arrive, they are nearly impossible to send away, the chemical byproduct of their endless gluttony (enabled by genetically-altered stomach enzymes) kills the local ocean, poisoning the fish that once supported honest fisherman like Captain Imamu, forcing them to turn to the United Nations for a meager livelihood, getting paid to clean up the mess made by wealthier countries that all scorned poor Africa until they needed African ships and crew to hunt their bioengineered monsters.

“我讨厌这些东西,”Nkechi一边说着,一边他的网拉到空中,从海中拉起另一个苍白的食塑鱼

“I hate these things,” Nkechi says, lifting a thrashing net high into the air as he pulls another pale plastic-eater from the Atlantic.

“我也是。”Abebi回答着,两眼看着那片被污染的海洋泛起的泡沫。“我也是。”

“Me too,” Abebi replies, eyes stinging from the spray of the infested and polluted sea. “Me too.”

塑料危机

The Plastic Crisis

众所周知,塑料对环境有害——一次性塑料的设计初衷是快速使用和抛弃,但它们销毁起来却难上加难。塑料垃圾一旦被埋进垃圾填埋场,可能需要数百年至数千年的时间才能完成生物降解,而且,在它们埋藏的过程中,有毒化学物质可能会扩散到附近社区的地下和水中,给居民带来诸多的健康问题。此外,当塑料非常缓慢地分解时,它们会分解成微粒,污染微生物和土壤,然后被鸟类、鱼类和小型哺乳动物摄入,此后通过层层捕食关系污染整个食物链;由于人类处于食物链的顶端,许多微粒最终会回到我们身边。这种高浓度的塑料微粒会对肠道内壁造成损害,或者从内部毒害人和动物,因为上述危险化学物质和塑料副产品会通过我们的身体系统运输。

It’s common knowledge that plastic is harmful to the environment— single-use plastics are designed to be quickly used and thrown away, but they aren’t destroyed quite as easily as they’re created. Once it reaches a landfill, plastic waste can take hundreds to thousands of years to biodegrade, and, while it sits there, may leak toxic chemicals into the ground and water of nearby communities, causing a wide array of health issues for residents. Furthermore, as plastic very slowly breaks down, it flakes into microparticles that contaminate tiny lifeforms and soil, which are then ingested by birds, fish, and small mammals and then gradually accumulate up the food chain as these animals are preyed upon by others; since humans are at the top of this food chain, many of these microparticles eventually find their way back to us. Such high concentrations of plastic particulates can cause damage to the intestinal lining, or poison people and animals from within as aforementioned hazardous chemicals and plastic byproducts spread through our internal systems.

但比起垃圾填埋场,塑料对海洋的危害更大。2015年进行的一项研究称,海洋中的塑料垃圾比之前估计的要多得多——超过1.5亿吨,并且平均每年都会增加800万吨。800万吨塑料足以覆盖34倍于曼哈顿大小的垃圾场,尽管最近全球回收行动有所增加,但海洋污染仍在以惊人的速度加剧。Ellen MacAuther基金会发表的一项研究预测,按照目前的速度,到2050年,全球海洋中塑料的含量将超过鱼类。

But despite the dangers that landfill-bound plastic presents to life around it, perhaps nowhere and nothing is as impacted by plastic waste as the Earth’s oceans. A study conducted in 2015 concluded that there is much more plastic waste in the ocean than formerly estimated— over 150 million tons, with an averaged 8 million more tons added every year. 8 million tons is enough plastic to cover an area 34 times the size of Manhattan ankle-deep in garbage, and, despite recent increases to global recycling initiatives, ocean pollution continues to pile up at an alarming rate; a study published by the Ellen MacArthur foundation predicted that, at current rates, the global oceans would contain more plastic than fish by 2050.

这就是《新时代渔业》中所展现的未来——塑料在海洋中泛滥,海洋环流裹挟着塑料形成了巨大的集中垃圾区,就像今天的太平洋垃圾带。不久后,“南半球”将负责处理大部分海洋塑料垃圾,因为它们的海域已经被塑料覆盖,而他们又无力通过国际途径争取权利。这与今天何其相似,这些不发达的国家一直在为气候变化负责,而人们大多误认为海洋中多数塑料垃圾来自亚洲。

This is the future explored in “New Age Fishing”— one where plastic has overrun global waters and oceanic gyres create huge zones of concentrated waste like the Great Pacific Garbage Patch of today. In this near-future, the “global south” is responsible for cleaning up most of the mess as their waters are choked to death by plastic waste and failed international solutions, similar to how, even in the current day, these countries are paying the price for climate change while being the least responsible, despite the common misconception that most of the plastic waste in the oceans comes from Asia.

《新时代渔业》为我们展现了一种潜在解决方案可能带来的意外后果:可食用塑料的鱼类及它们造成的物种入侵。为了应对污染问题,这些鱼类被释放到海洋中,但很快就变成了一种危险的入侵物种。在这种情况下,这些鱼类的捕捉和屠杀引起了全球的关注,但一旦它们被引入,被破坏的生物圈可能很难恢复。诚然,这是虚构的故事,但它是有原型的,那就是最近对食用塑料的生物体的研究,以及改变动物或生态系统以适应人类需求的探索历史。虽然将可分解塑料的微生物移植到鱼的胃里不太可能成为现实,但自然界中以塑料为食的生物可能会以一种更聪明的方式掌握对抗垃圾病的方式。

“New Age Fishing” explores the unintended consequences of a potential solution: The crux of the story hinges on plastic-eating fish, released into the ocean to combat the pollution problem, but quickly becoming a deadly and invasive species. In this scenario, the capture and destruction of these fish has become a global concern, but once free, introduced species can be very difficult to recover. It’s more fiction than fact, but inspired by recent research into plastic-eating organisms and the history of altering animals or ecosystems to suit human needs. While it’s unlikely that fish with plastic-decomposing microbes grafted into their stomachs will ever be reality, nature’s plastic-eating creatures may hold one of the many keys to combating the plague of waste— in a smarter way.

塑食者

Plastic Eaters

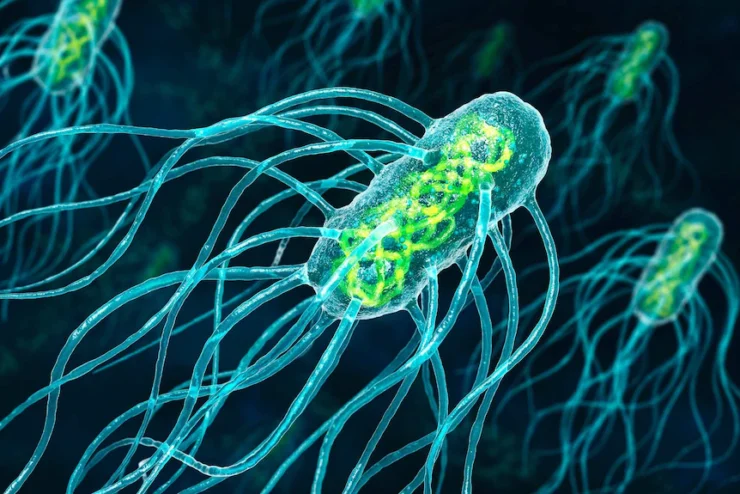

“新时代渔业”中处理塑料的重点是将吃塑料的微生物和酶引入现有鱼类的自然肠道菌群;然而,微生物并不是唯一食用塑料的生物。人们也在研究蜡虫消耗和分解塑料的能力。科学家们希望通过这两种生物(还有其他种类的昆虫或细菌)分离出能够分解塑料的酶,用来对付海洋和垃圾填埋场中堆积的塑料垃圾。

“New Age Fishing” focused on the introduction of plastic-eating microbes and enzymes into the natural gut flora of existing fish; however, microbes are not the only kinds of natural plastic eaters. Wax worms, too, are being studied for their ability to consume and break down plastic. Between these two (and, hopefully, other species of insects or bacteria) scientists hope to isolate the exact enzymes that enable this decomposition to employ against the plague of plastic waste building up in oceans and landfills.

自然疗法

Natural Cure

在科学界,塑食者的发现非常有创新性和开拓性,因为它仅限于非常少量的生命形式。对于蜡虫来说,获得这样独特的能力只是个偶然,因为它们在自然界的主要食物是蜂蜡。蜂蜡的分子组成与聚乙烯基塑料非常相似(后者约占全球塑料需求的40%),有证据表明,这种碳氢化合物分子是蜡虫消化的目标。当这些蠕虫吃蜂蜡和塑料时,防冻剂的主要成分乙二醇就会产生这个过程的副产品。科学家有理由认为,这些幼虫可以通过吃塑料生存,而不是仅仅漫无目的地咀嚼它们,而这对塑食者的生态部署有重要意义。

The discovery of plastic-eating organisms is relatively new and unexplored in the field of science, as it is limited to a very small number of lifeforms. For wax worms, this unique ability has evolved coincidentally because of their primary diet in nature: beeswax. The molecular make-up of beeswax is very similar to that of polyethylene-based plastics (about 40% of global plastic demand), and evidence indicates that this hydrocarbon molecule is the target of wax worm digestion. The byproduct of this process— ethylene glycol, a major component in antifreeze— is produced when these worms eat both beeswax and plastic, which scientists hope may point to signs that these larvae can survive by eating plastic, and aren’t just chewing through containers in search of freedom, opening doors for their potential ecological deployment.

另一种正在被研究的塑食者是一种地球海洋中的微生物。一项新研究表明,当把一些经过基因增强的微生物放在只有塑料垃圾的盐水罐中时,它们可以仅靠从塑料中分解的碳存活。五个月中,塑料已经被分解了不少——这第一步便给了人们巨大的希望。下一阶段的研究将集中在如何有效地在地球的海洋中部署这些微生物,尽管它们已经存在于海洋中,但还没有对塑料垃圾的分解产生显著影响。

The second form of plastic-eating organism currently being researched is a species of microbe already found in the Earth’s oceans. Through a recent study, scientists discovered that, when placed in a saltwater tank with nothing but plastic waste, a strand of the microbes that had been genetically-enhanced could survive solely on the carbons that they broke down from the provided plastics. Over a course of five months, the plastic underwent a significant loss of mass as it was slowly consumed by the microbes— a very promising first step. The next phase of research will focus around how to effectively deploy these microscopic organisms in Earth’s oceans, where they already exist but are not yet making a considerable dent in plastic waste.

入侵物种

Invasive Species

通过使经过基因增强的微生物或蜡虫分泌可以分解塑料——这一堆积在海洋中和垃圾填埋场里的最具危害性和顽固性的有机垃圾——的酶,从而完成清除塑料这一人类无法完成的任务,这个想法听起来很诱人。同样的想法以前也有过,比如英国公司Oxitec获得许可,在得克萨斯州和佛罗里达州释放转基因蚊子,以应对寨卡病毒蔓延引起的恐慌。这些蚊子将不育基因传给它们的雌性后代,在几代中大大减少了蚊子的总数。这一想法将类似于将基因增强的微生物或蜡虫释放到野外:它们将不断繁殖,最终创造出一个经过增强的生物体的野生种群,以更快地处理塑料垃圾。

On the surface, “genetically enhancing” microbes or wax worms to produce more plastic-devouring enzymes and then unleashing these hungry creatures on garbage piles does seem like an enticing idea— these organisms are able to organically break down one of the most toxic and long-lived pollutants currently choking our oceans and poisoning landfills, which is something we, as humans, cannot do. The same general idea has been practiced before, such as when British company Oxitec secured permission to release genetically-modified mosquitoes in Texas and Florida to combat mounting fear of Zika outbreaks. These mosquitoes passed down an infertility gene to their female offspring, greatly reducing the overall population over several generations. The idea would be similar with genetically-enhanced microbes or wax worms released into the wild: they would breed and multiply, eventually creating a wild population of enhanced organisms to faster tackle plastic waste.

但并不是所有通过人类工程解决生态问题的方法实行起来都像Oxitec释放蚊子那样顺利。在历史上,有几次外来生物被释放到非本来的生态系统中(为了应对全球问题,这些微生物和蜡虫就必须如此),但它们过量繁殖,造成了不可预见的破坏。例如,将尼罗河鲈鱼引入维多利亚湖;引进尼罗河鲈鱼原本是为了支持钓鱼运动和鱼类渔业,但它们很快就失去了控制,破坏了自然食物链,导致该湖中500多种原生鲤科物种的种群数量下降甚至灭绝。生态平衡的迅速破坏导致维多利亚湖加速富营养化,藻类爆发式增长,在水中形成了无氧的“死区”。几乎没有人预见到这种意想不到的副作用,即使是那些反对引进尼罗河鲈鱼的人。现在,就像在《新时代捕鱼》中一样,渔船成群捕获鲈鱼,希望减少它们的数量,但一旦在生态系统中建立了种群(无论多么具有破坏性),入侵物种就几乎不可能被清除。

But not all human-engineered solutions to ecological problems have worked as smoothly as the Oxitec mosquito release. Several times in history, organisms released into non-native ecosystems (as these microbes and wax worms would have to be, to combat the global problem) proliferate beyond control or cause unforeseen damage. Take, for instance, the introduction of Nile perch into Lake Victoria; initially intended to bolster sport fishing and stock fisheries, Nile perch soon bred out of control, disrupted natural food chains, and led to the decline and extinction of 500+ species of cichlid native to the lake. This rapid unbalance led to the accelerated eutrophication of Lake Victoria, leading to an algae bloom and creating oxygenless “dead zones” in the water. This unintended side effect was one that few— even those who opposed the introduction of Nile perch— foresaw. Now, like in “New Age Fishing”, fishing ships capture the perch in droves, hoping to deplete their numbers, but once established (however disruptively) in an ecosystem, invasive species can be almost impossible to remove.

和尼罗河鲈鱼一样,很难预测将非本地塑食动物释放到像全球海洋这样复杂而广泛的生态系统中可能会造成多大的破坏,尤其是这种生物的基因并不常见于自然界中。虽然微生物或蛾类幼虫不太可能像尼罗河鲈鱼在维多利亚湖较小的鲷鱼中那样,在食物链的顶端占据一席之地,但它们仍然会对当地的生物多样性构成威胁。如前所述,塑料分解的主要副产品之一是乙二醇,它在高浓度时具有很高的毒性,可能会由于微生物不受管制地消费塑料而导致海洋中出现有毒区域,类似于缺氧的维多利亚湖。乙二醇和其他微生物分解塑料的副产品对珊瑚礁尤其危险,它们会使珊瑚礁生病,而珊瑚礁是海洋生态系统的重要组成部分,在现在的情况已经不容乐观。但是,即使蜡虫和微生物被证明不会毒害它们周围的环境,几乎可以肯定的是,试图设计生物体来解决它们最初进化时不具备的问题,也会产生不可预测的副作用。因此,虽然塑料污染是一个紧迫的问题,我们也应该在这些未经测试的生命形式被迅速部署到全球之前进行批判性思考,并可能考虑应用酶降解塑料,而不涉及破坏已经不平衡和脆弱的地球生物多样性。

Like the Nile perch, it’s difficult to predict the full extent of damage that releasing non-native plastic-eaters into an ecosystem as complex and widespread as the global oceans might cause, especially with such a new and relatively unknown biological process at the heart of it. While it’s unlikely that microbes or moth larvae will carve themselves a niche at the top of a food chain like Nile perch did among the smaller cichlids of Lake Victoria, they can still pose a threat to native biodiversity. As earlier mentioned, one of the primary byproducts of plastic decomposition is ethylene glycol, which can be highly toxic in high concentrations, possibly leading to poisonous zones in the ocean from unregulated microbe consumption of plastic, similar to the oxygen-depleted Lake Victoria. Ethylene glycol and other plastic or microbe byproducts are especially dangerous and disease-causing to coral reefs, a vital part of the oceanic ecosystem that’s already on the decline. But even if wax worms and microbes are proven not to poison their surrounding environment, there are almost certainly unpredictable side effects to trying to engineer organisms to tackle a problem they were not originally evolved to handle. So while plastic pollution is a pressing issue, we should think critically before the rapid deployment of these untested lifeforms, and possibly consider applications for enzyme-degradation of plastic that doesn’t involve disrupting the already unbalanced and fragile biodiversity of Earth.

应用

Application

总的来说,尽管塑食生物的发现令人兴奋,但要让它们投入使用还有很长的路要走,它们很可能不会在短期内被部署下去,因为科学家们还需要进一步研究它们是如何分解塑料的。也许微生物和蜡虫可以不被释放到地球的海洋和垃圾填埋场,而是进入大型的、受控的实验室中,在那里,它们降解塑料的副产品(包括二氧化碳、染料和毒素)可以被收集和回收,而不是泄漏到环境中。这种处理塑料垃圾的方法肯定有助于遏制地球上充斥着的塑料垃圾,但专家们认为,这些塑食者只是解决塑料问题的一种途径,而不是我们对抗塑料污染的唯一方法。总部位于法国的Carbios公司正在与制造商和社区合作,回收现有的塑料垃圾,并开发更环保的植物基塑料,以取代一次性聚酯。但即使是这些举动,以及通过微生物分解塑料的方法也只是为了处理已经造成的污染。为了彻底解决地球上的海洋和垃圾填埋场中的塑料,我们需要采取积极主动的立法和生活方式的改变,以阻止废料进入自然环境。尽管困难重重,但这样的改变在长远来看更经济、更清洁、对全球更有益——这需要社区、国家和企业的帮助,逐步淘汰全球塑料生产,但如果我们能做到,我们可能会看到吃塑料的微生物的艰苦工作在清理地球方面产生不同的效果,因为一旦垃圾无法快速增加,它们就会帮助分解已经开始堆积在水道和垃圾填埋场的垃圾。关键是他们不需要独自工作——就像生态系统是由无数生物,每个生物都在扮演着重要角色,维持着生态平衡,解决塑料污染这一全球性危机将需要人们在日常生活中清理、回收塑料并使用塑料替代品,而不是一边释放一群塑食微生物和虫子到地球上的海洋中去,一边还在不断把垃圾扔进下水道——它看起来简单快捷,但最终会带来巨大危险——让我们在日常生活中,无论是在家里还是社区里,都减少和回收利用塑料,为塑料问题的解决贡献一份力量。

Overall, despite much excitement around their discovery, plastic-eating organisms have a long way to go, and will likely not be released into the wild in the near future as scientists continue to research the process by which these lifeforms break down plastics. Instead of being unleashed into the Earth’s oceans and landfills, microbes and wax worms may help from large, controlled laboratories, where the byproducts of their plastic degradation (including carbon dioxide, dyes, and toxins) can be collected and recycled, rather than leak out into the environment. This method of disposal will certainly be helpful in the ongoing war on plastic waste filling up the planet, but rather than being our sole approach to combating plastic pollution, experts agree that these plastic-eaters are only part of the solution. Companies like French-based Carbios are partnering with manufacturers and communities to recycle preexisting plastic waste and to develop more ecologically-friendly, plant-based plastics to replace single-use polyester. But even these promising developments, along with microbe decomposition, are an effort to clean up the mess that’s already been made. In order to fully save the Earth’s oceans and landfills, proactive legislative and lifestyle changes will need to be implemented to stop the flow of waste into the environment. Though difficult, such changes would eventually be cheaper, cleaner, and globally beneficial— it would take the help of communities, countries, and corporations to phase out global plastic production, but if we can, we may see the hard work of plastic-eating microbes make a difference in cleaning up the Earth as they help to decompose what has already begun to pile up in our waterways and landfills, once that waste is no longer being replaced as fast as it can be removed. The key is that they can’t do it all by themselves— just as ecosystems are made up of countless organisms, each playing a key role in maintaining equilibrium, the solution to the global crisis of plastic pollution will require multiple means of clean-up, recycling, and utilizing plastic alternatives in everyday living. So rather than unleashing an army of plastic-eating microbes and worms into Earth’s oceans while continuing to dump millions of tons of waste into our waterways every year— a seemingly easy but ultimately dangerous “quick fix” to the problem— let’s all do our part to spare the plastic-eaters the trouble and reduce, reuse, and recycle in our own homes, communities, and daily lives.

翻译:墨淞凌@STARSET_Mirror翻译组

审校:CDN@STARSET_Mirror翻译组