by Samuel Gilbert

Mob mentality.

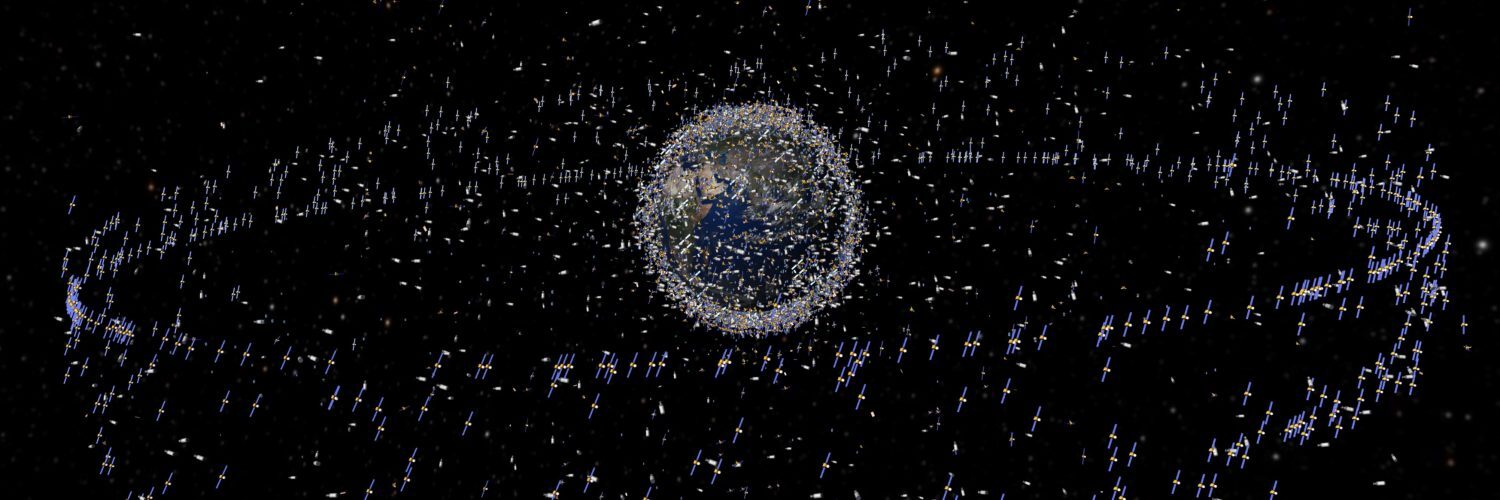

The skies are crowded.

Every year the world becomes more connected. New technologies are shrinking the vast distances that once made global communication slow and difficult. The advent of satellite communication has brought high speed internet to rural communities, provided entertainment to the masses, and allowed the most precise navigation imaginable.

Science, too, has benefitted from the advances and multiplication of satellites. Telescopes in orbit look deep into the starfield, while others look down to Earth, measuring ice fields, subterranean water supplies, coastal erosion, and desertification.

The militaries of the world use the ultimate high ground of orbital position to keep wary gazes measured against each other. Countries around the globe use satellites for reconnaissance, surveillance, communications, navigation, and meteorology. For example, the US’s Improved CRYSTAL satellite provides ground images of targets in real time.

The proliferation of satellites has even reached into the elementary school curriculum. Here and there around the world, students create small scale experiments which can be launched into orbit or sent to the International Space Station via nanosats. NASA used satellites to conduct workshops around the world where students from more than 100 countries could submit their weather and climate observations to the GLOBE Web site.

But all these benefits come at a cost: the overcrowding of orbital spaces.

Lost in the crowd.

There are currently over 2,000 active satellites in orbit around the Earth and just as many inactive ones circling the globe. In the future, that number is expected to continue growing at an astonishing rate. As more countries and corporations seek a foothold in the sky, the amount of safe orbital space shrinks.

The International Telecommunications Union (ITU) may assign orbits for commercial satellites, and national space agencies may determine the orbits for their own devices; however, those assignments can only control traffic flow. These bodies have not–and do not–appear to have any immediate plans to control the number of placements in orbit. What’s more, a number of private, non-state actors placing nanosats in orbit is also expected to increase.

The relatively low cost of producing and launching satellites means that immediate space around the Earth is now accessible in a way it never was before. This has allowed private companies and billionaires to pursue their own interests. For example, Elon Musk has promised to deliver free internet via a nanosat mesh in orbit above the Earth. While the launch of the first such cluster was success and Musk’s intentions may be noble, his method may end up causing more harm than good.

With so many bodies being added into orbit in such a quick pace, the threat from space debris increases. There is already a large amount of debris in orbit, from anti-satellites weapons testing, to decommissioned objects cluttering up space, to pieces of those objects which have detached in an uncontrolled manner.

Recently, the ISS was threatened by one such cluster of debris, it was not the first time such a near-miss occurred and it will not be the last. Moreover, the threat is not just one that exists in the small scale and near-misses around the ISS. There is a larger threat looming: the Kessler Syndrome.

Critical masses.

Proposed by NASA engineer Donald Kessler in 1978, the Kessler Syndrome discussed the problem of space debris, as well as the lack of will to address it. Kessler Syndrome is described as such: the more bodies that are in orbit around the Earth, the more likely there will be a collision. If that collision were to happen in a sufficiently crowded orbital path, the chain reaction of collisions could radiate outward, poisoning other orbital paths. If that were to occur, access to space could potentially be cut off. It will not simply be a matter of difficult launches but, rather, a complete blocking of all possible launch points.

Without the ability to safely launch in orbit, those devices not destroyed in the initial reaction would fall out of repair and become unusable. The capacity to continue exploring the Solar System would be cut off, as would any chance of interplanetary settlement.

The blue marble would become a blue cage.

Crowd control.

The alarms have, of course, been ringing about this problem since the early days of space flight. However, like climate change, the slow simmer of the crisis leading to a disastrous boil-over has been mostly ignored.

The canon of space law is a tangled web of cold war doctrine and post hoc addendums combined with a patch work of national laws and regulations.There is no overarching law to deal with space debris. So difficult is the problem that many aspiring space lawyers tangle with hypothetical legal scenarios based around resolving damages caused by space debris in moot court to prepare for the day when those real cases will be on the dockets. Determining not just fault, but even what legal body to approach for a redress of grievances, is a difficult problem as well. This all is compounded by an overlapping network of national and international regimes codified by various treaties and laws that have not been seriously reformed since the Reagan Administration.

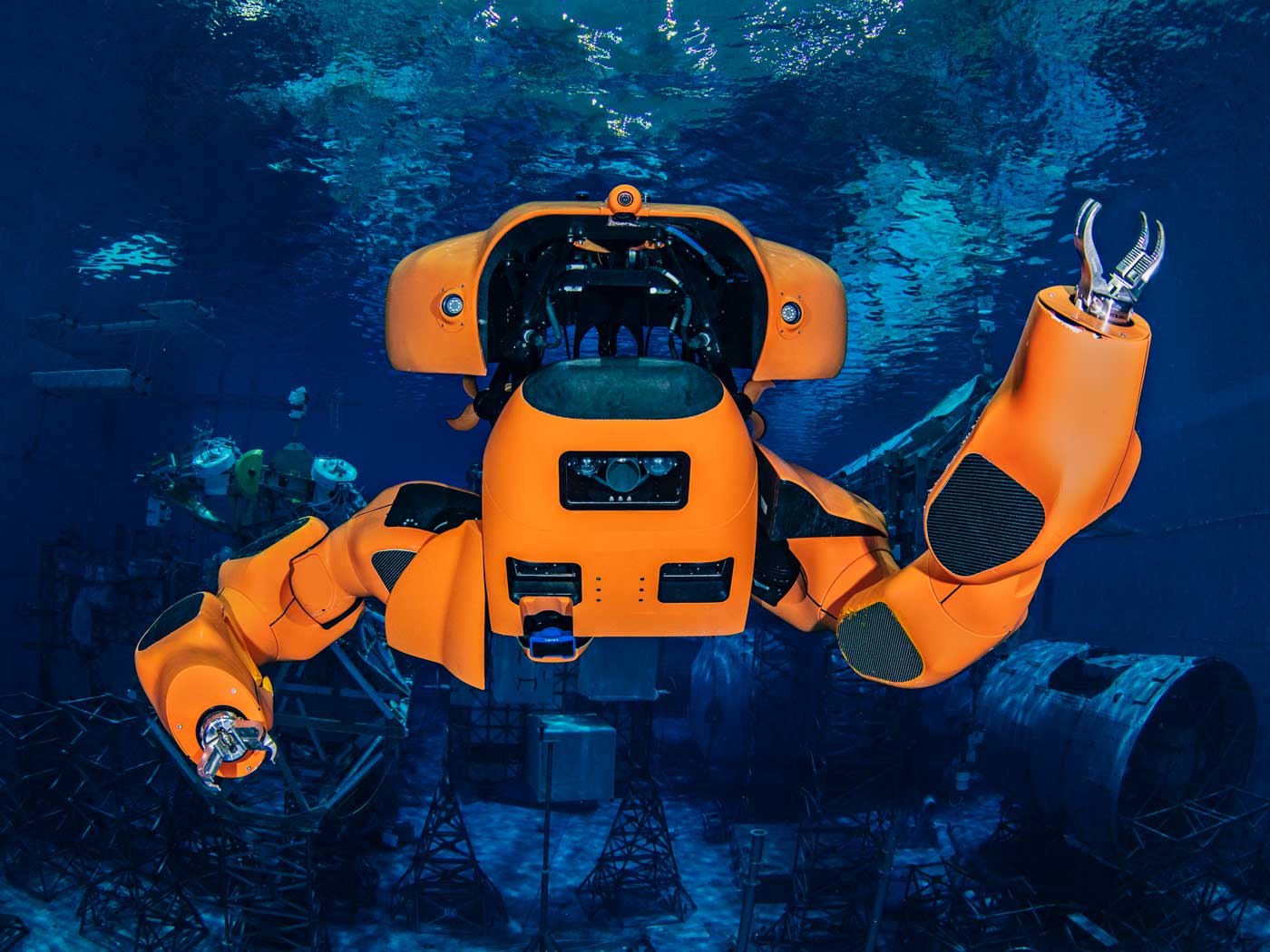

Legal issues aside, there are technical problems, too. Much academic ink has been spilled devising various ways to make satellites eco-friendly. Tethers that slowly pull satellites into the atmosphere to burn up was one proposed method, but one that has yet to gain much traction. How to deal with the debris currently in orbit is another problem altogether, and has garnered solutions ranging from ground-based lasers to orbital nets that collect bodies. So far, however, no national body has devised a method to fund this effort on an international scale.

The problem of space debris is persistent. It will remain a problem and a potential disaster for as long as humanity pushes towards the stars. There is hope, however, that it will never come to Kessler’s dire Syndrome. Despite the lack of action in the past, there are increasing calls from younger members of the aerospace community to deal with the problem now while it is still manageable, rather than later when it becomes untenable. Several working groups of young attorneys and industry experts are pushing for a new set of treaties and programs to govern the way debris is handled and disposed. This new generation of leaders is hopeful to ensure that Earth remains a cradle and not a cage.