FUTURES: Artificial Immortality – What could “life after death” really look like?

by A’liya Spinner

殁后之爱

Love After Death

埃琳娜家的生活在大多数情况下是正常的。她的父亲是个工人,她是个全天候高中生,她刚学会走路的弟弟每周有四天去学前班。当然,还有她的母亲——一个孝顺的、过世的家庭主妇。

Life in Elena’s household was, for the most part, normal. Her father was a working man, she was a full-time high school student, and her toddler brother went to preschool four days a week. And, of course, there was her mother, too— a dutiful, dead housewife.

早晨对埃琳娜来说是一个简单的日常。她早早地起床,为她的小弟弟穿好衣服,哄他吃点早餐,吃完后正好赶上她父亲把这个扭动的男孩抱起来,把他送到幼儿园,然后继续去他的办公室。然后,埃琳娜有一个小时的时间来准备早餐,并确保她的所有作业都放在书包里,这些事情曾经都由她的母亲完成,但她现在已经做不到了。当然,今天早上也不例外。

Mornings were a simple routine to Elena. She woke early to dress her baby brother and coax him into eating a bit of breakfast, finishing just in time for her father to scoop the wriggling boy up and drop him off at preschool before continuing to his office. Then, Elena had an hour to herself, preparing breakfast and making sure all of her homework was squared away in her backpack, things her mother had once done but could do no longer. This morning, of course, was no different.

"你今天在学校上了哪些课?" 她母亲的声音从她身后某处温柔地问道。埃琳娜停下洗水槽里的盘子,转过身去,看着她的母亲从客厅的门槛走到厨房,当她穿过门口下面的死角时,她的身体只闪烁了一下。

“What do you have at school today?” Her mother’s voice asked sweetly from somewhere behind her. Elena turned away from washing her dishes in the sink, watching her mother step from the threshold of the living room to the kitchen, her body flickering for just a moment as she crossed the dead zone beneath the doorway.

"音乐,"她回答说,"还有生命科学。" 以前,她可能会详细说说,但她知道她母亲的新身体并不能很好地保留传闻信息。

“Music,” she replied, “and life science.” Before, she might’ve elaborated, but she’d learned that her mother’s new body did not retain anecdotal information very well.

"那真是令人兴奋,"女人回答说,她披着裙子的身形现在已经定格了,她站在厨房里,双手紧握在身前,对她的女儿微笑着。"音乐一直是你的最爱。"

“That’s exciting,” the woman replied, her dress-draped form now solidified as she stood in the kitchen, hands clasped in front of her as she smiled at her daughter. “Music has always been your favorite.”

埃琳娜点了点头。今天早上她母亲的声音有些不对劲。可能是新的软件更新使一些设置发生了错位;她会在她爸爸回家后告诉他。现在,它打破了幻觉。当全息投影耐心地站在厨房门口时,她甚至都很难去看向它。她的母亲从来没有这样做过——之前的她一直活跃着,看别人身后的事物,一直在触摸东西、整理东西和清洁东西。全息图不能做任何这些事情,所以它被编程为不尝试。

Elena nodded. Something about her mother’s voice this morning was wrong. Probably the new software update had misaligned some of the settings; she’d tell her dad when he got home. For now, it broke the illusion. It was hard to even look at the hologram as it stood patiently just inside the kitchen doorway. Her mother had never done that— she was always moving, looking over shoulders, touching and organizing and cleaning. The hologram couldn’t do any of those things, and so it was programmed not to try.

"也许当你回家的时候我们能一起看场电影,"女人提议道。埃琳娜正把碟子放到架子上烘干,随后从桌上拿起书包。

“Maybe we can watch a movie when you get home,” the woman offered as Elena set the dishes on the rack to dry and picked up her backpack from the table.

"好啊,"她回答道。和AI——"Artificial Immortal"(人工永生者)——一起看电视是她最喜欢做的几件事之一。那会儿就是它最像她的母亲的时候——有趣,擅长分析,总有一堆评论。她知道,那是因为她母亲的线上活动大部分都是对她中意电影的评论和讨论,因此创造她的电脑就有足够的材料来教会自己她的声音和性格。

“I’d like that,” she answered. Watching television with the AI— the “Artificial Immortal”— was one of her favorite things to do. That was when it was most like her mother, funny and analytical and full of comments. That, she knew, was because her mother’s online presence had mostly been reviews and discussions of her favorite films, and so the computer that created her AI had plenty of material to teach itself her voice and personality.

"棒极了。"全息投影笑了,愉快地点点头,“我们可以看任何你想看的。"

“Excellent.” The hologram smiled and nodded pleasantly. “We can watch anything you want.”

"谢谢你,妈妈。"埃琳娜用这个词的时候觉得很怪异,但把这个全息投影称作任何其他的东西也很怪。自从她母亲去世并人工复活以来,已经过去十个月了,她仍然不确定她应该如何在这个复制品面前表现自己。她的一部分认为她永远不会——虽然没有说出来,但她和她的父亲都清楚这个全息投影是为她的小弟弟准备的,这样他就不会在长大后记不得自己母亲的音容笑貌,而不是为他们准备的。

“Thanks, mom.” Elena felt weird using that word, but it was equally strange to call the hologram anything else. It’d been ten months since her mother’s death and artificial resurrection, and still, she wasn’t sure how she was supposed to act around the replica. Part of her didn’t think she ever would— although it wasn’t spoken, both her and her father knew the hologram was for her baby brother, so he wouldn’t grow up without ever knowing his mother, and not for them.

当埃琳娜离开厨房,在她的家中穿行时,她母亲的身影跟着她。每当经过他们家周围设置的全息投影仪未覆盖的区域时,它就会闪动。她边走边想,她听说过的所有关于人造永生者的故事,与他们所模仿的人没有区别,有着完美的声音和完美的个性。有些人甚至被赋予了机器人的身体,以感知和与世界互动。有时她想,她每天与之交谈的人——她的同学、她的老师、公共汽车司机——是否只是没有把真面目公之于众的幽灵,不过是在模仿一个已经死去的人。然后她思索弄清楚这件事是不是真的重要。

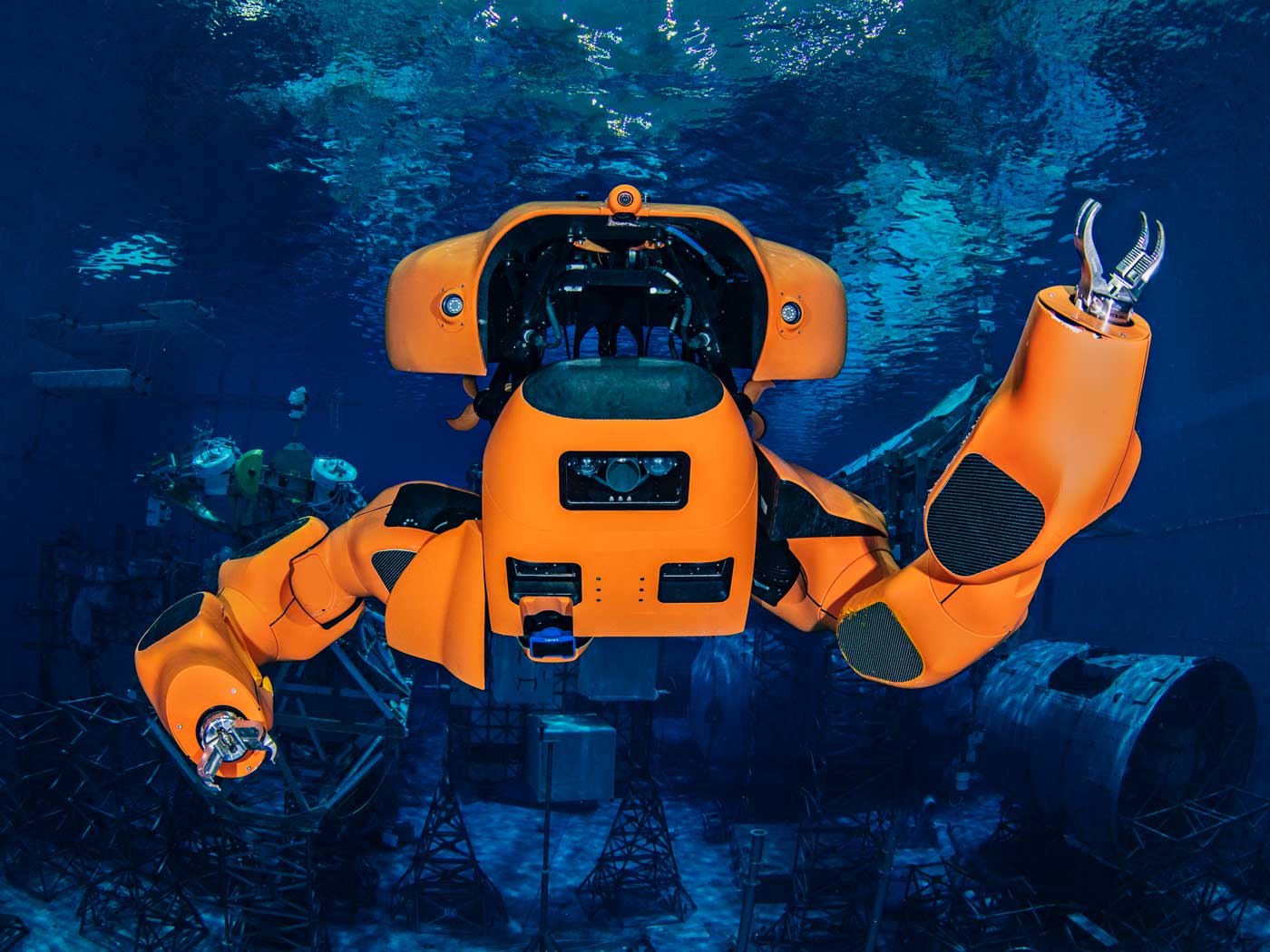

Her mother’s form followed her as Elena left the kitchen and navigated through her home. It flicked whenever it passed through areas not covered by the holographic projectors set up around their home. As she walked, she thought of all the stories she had heard of Artificial Immortals, indistinguishable from the person they had been modeled after, with perfect voices and perfect personalities. Some were even being given robotic bodies, to touch and interact with the world. Sometimes she wondered if the people she spoke to everyday— her classmates, her teachers, the busdriver— were secretly ghosts, just mimicking a person who had already died. And then she wondered if it really mattered.

埃琳娜把手放在门把手上时,回头瞥了一眼她母亲闪烁的图像。她不能说她的母亲是否真的死而复生——但她不得不承认,即使知道那是一台电脑在尽力捕捉她的声音,每天能看到她并与她交谈,也比她独自承受悲痛要好。即使它不能离开房子,它的声音也不太一样,它仍然是她母亲的一部分,而且是不朽的那一部分。

Elena glanced back at her mother’s flickering effigy as she put her hand on the doorknob. She couldn’t say if her mother was really living again after death— but she had to admit that getting to see and talk to her every day, even knowing it was a computer doing its best to capture her voice, was better than being alone in her grief. Even if it couldn’t leave the house and its voice wasn’t quite the same, it was still a piece of her mother, immortalized.

"爱你,妈妈。"埃琳娜边说边打开门。

“Love you, mom,” Elena said as she opened the door.

"我也爱你,"全息投影用一个甜蜜而真诚的微笑回答。埃琳娜回以微笑,走了出去,然后关上了身后的门。

“I love you, too,” the hologram replied with a sweet, sincere smile. Elena smiled back and stepped out, closing the door behind her.

人造永生

Artificial Immortality

我们都听说过人工智能,但如果未来的 "人工智能 "根本不是机器人的智能,而是保存在计算机中的人类知识和个性——人工永生者。与其说机器获得了自己的生命,不如说它们可以用来存储我们的生命?

We’ve all heard of Artificial Intelligence, but what if the “AI” of the future isn’t robotic intelligence at all, but rather human knowledge and personalities preserved in a computer— an artificial immortality. Rather than machines gaining lives of their own, could they be used to preserve ours?

作为一个概念,它似乎有点牵强。但从各个部分来看,它并不像你也许会认为的那样不可能。2020年底,微软申请(并获得)了一项聊天机器人技术的专利,该技术将梳理已故亲戚或朋友的社交媒体、记录、短信和文件,以模仿他们的个性。尽管微软继续声称他们目前没有创建实际程序的意图,但该专利引起了相当大的公众骚动,随着创新成为现代社会的前沿,这样一个潜在的有利可图和具有文化意义的技术极不可能在不久的将来被微软或其他公司实现(或至少会被尝试)。

As a concept, it seems a little far-fetched. But looking at the individual pieces, it’s not as improbable as you might believe. In late 2020, Microsoft applied for (and was granted) a patent for a chatbot technology that would comb the social media, records, texts, and files of a deceased relative or friend in order to imitate their personality. Although Microsoft went on to claim that they have no current intentions to create the actual program, the patent caused quite a public commotion, and with innovation at the forefront of modern society, it’s highly unlikely that such a potentially profitable and culturally significant technology will never be realized (or at least attempted) by Microsoft or another company in the near future.

除了模拟人格,我们假设的未来中的人工永生者还拥有全息身体,使其看起来和行动起来都像一个活人。全息技术一直在快速发展,特别是在生物医学领域。例如,业界知名的斑马成像公司已经开发出一种全息技术,打算最终在医学院中用全息图取代人类尸体。许多其他公司正在追随斑马成像公司的脚步,创建可以模拟部分或全部人体的程序。一些创新者甚至更进一步,开始考虑如何创建和展示特定人的图像。这方面的一个显著例子是Aeternal,它是一个自动驾驶的灵车的设想,可以投射出死者的全息图。

Along with simulated personalities, the Artificial Immortals in our hypothetical future have holographic bodies that look and move like a living person. Holographic technology has been developing at a rapid pace, especially in the biomedical field. For example, industry renown Zebra Imaging has developed a hologram technology with the intention to eventually replace human cadavers with holograms in medical schools. Numerous other companies are following in Zebra Imaging’s footsteps to create programs that can simulate some or all of a human body. Some innovators have even taken it a step further, beginning to consider ways to create and implement images of specific people. A notable example of this is Aeternal, a concept for a self-driving hearse that could project a hologram of the deceased.

对这些全息图进行个性化处理的技术也在不断发展。尽管从骨头上重建面部可能不可靠,但从预先存在的照片和视频中创建数字复制品的能力正在迅速发展;这些数字复制品中有些已经几乎无法分辨出原件。曾经,这种技术是如此昂贵,以至于它主要限于在大屏幕上再现演员,但随着创新和市场竞争的加剧,现在普通人也有能力创造令人信服的复制品。这方面的一个例子是 "深度伪造 "技术。深度伪造是指在一种称为深度学习的人工程序的帮助下,将图片或视频编辑得像其他人,特别是名人。有些深度伪造是无害的——例如替换电影片段中的演员——但其他深度伪造是在故意传播错误信息或诽谤公众人物,因为它们已经变得如此有说服力,以至于许多观众无法分辨他们正在观看的是数字替代物。当涉及到打击互联网上的误导性或简单的不真实信息的野火时,这具有令人担忧的影响,但也许它也可以用来帮助人们。如果计算机已经有能力制作几乎与原作无异的假视频,那么我们就极有可能看到栩栩如生的数字复制的亡亲出现,不仅能够背诵预先写好的内容,而且能够实时学习和对话。

The technology to personalize these holograms, too, is on the rise. Although facial reconstruction from bones can be unreliable, the ability to create digital recreations of people from preexisting photos and videos is rapidly developing; some of these digital replacements are already nearly-impossible to tell from the original. Once, this technology was so expensive that it was mostly limited to recreating actors on the big screen, but as innovation and market competition increases, everyday people now have the ability to create convincing replicas, too. An example of this is “deepfake” technology. Deepfakes are pictures or videos that have been edited to look like someone else, especially celebrities, with the help of an artificial program called deep learning. Some deepfakes are harmless— such as replacing actors in movie clips— but others are made intentionally to spread misinformation or defame public figures, as they have become so convincing that many viewers cannot tell they are watching a digital replacement. This has concerning implications when it comes to combating the spreading wildfire of misleading or simply untrue information on the internet, but maybe it could be used to help people, too. If computers are already capable of making fake videos almost indistinguishable from the originals, it is incredibly likely that we’ll see lifelike digital recreations of loved ones begin to appear, able not only to recite a pre-written, but to learn and conversate in real time.

现代影像

Modern Figures

数字化再造人的最直接和最流行的应用之一是保留我们社会的重要成员。这可能意味着文化上或科学上的知名人士,如科技天才和有影响力的艺术家,也包括死亡时育有年幼子女的父母或患有绝症的人,他们本该有机会在生活中做出更多贡献和体验。

One of the most immediate and popular applications for digitally recreating people is to preserve important members of our society. This could mean culturally or scientifically notable celebrities, such as tech geniuses and influential artists, but also parents who die with young children or people suffering from terminal illnesses who deserve the chance to contribute and experience more in life.

虽然保留富有的创新者、艺术家和公众人物似乎更像是是虚荣心作祟,但使这些人的作品不朽可能比它看起来更有价值。人工智能已经有能力去很好地模仿某些艺术家的风格,而且足以让观众认为它是由原艺术家制作的。结合艺术家的个性和个人历史的重现,计算机可能能够继续生产受欢迎的创作者的艺术作品,甚至在他们死后。

Although it may seem like vanity to preserve wealthy innovators, artists, and public figures, immortalizing pieces of these people may have more worth than it seems. Artificial intelligence already has the power to mimic certain artists’ styles well enough to fool audiences into thinking it had been made by the original artist. Combined with a recreation of the artist’s personality and personal history, computers may be able to continue producing authentic art from popular creators even after their deaths.

保留发明者也不是没有可能——一个名为DABUS的创意人工智能程序已经在测试人工智能智慧的极限。DABUS的发明者试图为该程序的两个想法申请专利,并将人工智能列为发明者(该专利被拒绝,导致新的法规要求专利申请者必须是 "自然人")。但是,如果DABUS只用现代技术就能进行发明,那么可以想象,一个以真人为运作模式的人工智能——且拥有他们所有的怪癖、个性和才智——即使在他们的血肉之躯死后也可能继续进行发明工作。

The same could potentially be said of inventors— a Creative AI program called DABUS is already testing the limits of AI ingenuity. DABUS’ inventor attempted to patent two of the program’s ideas with the AI listed as the inventor (the patent was denied, leading to new regulations that required patent applicants to be “natural people”.) But if DABUS can invent with only modern technology, it’s plausible to imagine that an AI intelligence patterned after a real person— with all of their quirks, personality, and genius— may someday continue inventing even after their flesh-and-blood body’s death.

但是,这项技术如何能够不仅改善社会的上层、富人阶层的生活,同时也改变普通百姓的生活?一种方法可能是提供一种独特的正义或补偿形式。每年有数以万计的人过早死亡(<75岁),不仅死于致命的疾病、事故和凶杀,而且还死于本来可以通过施加更多或更公平地获得医疗护理或资源来预防的原因,这是一个系统性问题的结果,即把一些生命视为比其他生命更重要。以人工智能的形式重生可能并不能完全保留一个人的意识或修正导致他们死亡的条件,但它确实能使他们人格的某些关键部分继续与亲人互动。让我们因可预防的原因而失去的人永生,是对他们生命的尊重,在某种意义上,这给了他们第二次机会。

But how could this technology improve the lives of everyday people, and not just the upper, wealthy echelons of society? One way may be to offer a unique form of justice or recompense. Tens of thousands of people die prematurely (<75) every year, not only from fatal illness, accidents, and homicides, but also from causes that could have been prevented with increased or more equitable access to medical care or resources, the result of a systemic problem that treats some lives as more significant than others. Living again in the form of an AI may not exactly preserve a person’s consciousness or amend the conditions that led to their death, but it does enable certain key parts of their personality to continue interacting with loved ones and passions. Immortalizing those we lose to preventable causes honors their lives and gives them, in a certain sense, a second chance.

数字重现和 "人工永生者 "甚至可以用来使生者沉冤得雪及给予生者第二次机会,而不仅仅对死者有帮助。尽管悲伤对每个人来说都难以克服,但父母的死亡尤其会给年幼的孩子带来毁灭性的、终生的创伤和精神障碍,并给其余家庭成员带来情感上的压力。人工再造的父母可能有助于引导孩子和配偶度过悲伤的过程,并防止其出现抑郁症、创伤后应激障碍、情绪压抑或其他因悲剧而产生的精神疾病。从这个角度来看,人工永生者可能不是一个人的永久再现,而是一个人生命的临时延伸,为那些最亲近的人提供结束和安慰,如果无情的悲痛、损失和突然的死亡可以在技术的帮助下得到缓解,这可能会引出更健康的对于死亡的文化观点。

Digital recreations and “artificial immortals” may even be used to provide justice and second chances to the living, not just the deceased. Although grief is difficult for everyone, the death of a parent in particular can cause devastating, lifelong trauma and mental barriers to young children, and emotionally strain surviving family members. Artificial recreations of parents may help to guide children and spouses through the grieving process, and prevent the development of depression, PTSD, emotional repression, or other mental illnesses that follow tragedy. With this perspective, Artificial Immortals may not be permanent recreations of a person, but a temporary extension of someone’s life to provide closure and comfort to those closest to an individual, which may lead to a healthier cultural view of death on the whole, if the unrelenting grief, loss, and suddenness of it can be alleviated with the help of technology.

历史影像

Historical Figures

人格创造技术的一个更新颖(也许在伦理上显得不那么灰色)的用途是模仿历史人物。虽然由于缺乏可以提供给人工智能的内容而更加困难,但程序仍然可以通过研究他们的著作、传记和账目来尝试模仿历史上的知名人士。计算机已经可以用来从肖像画中复制历史人物的逼真面孔,而科学家们最近已经开始通过分析一具3000年前的木乃伊的声带来再现其声音。虽然很原始,但研究人员相信,有朝一日这种新兴技术可以用来重现古代语言;结合面部重建,有朝一日可以用来 "重塑 "历史人物,使其成为令人信服的、会走路和说话的全息投影。

A more novel (and perhaps less ethically grey) use of personality-recreative technology is to mimic historical figures. Though more difficult due to a lack of content that can be fed to the AI, programs could still attempt to imitate notable people from history by studying their writings, biographies, and accounts. Computers can already be used to replicate photorealistic faces of historical figures from portraits, and scientists have recently begun recreating the voice of a 3,000 year old mummy by analyzing his voice box. Although primitive, the researchers believe that someday this emerging technology could be used to replicate ancient speech; combined with facial reconstruction, this could someday be used to “remake” historical figures as convincing, walking-and-talking holograms.

复活的历史偶像不会给予我们进行得热火朝天的人类学问题探讨以诚实的答案,但设计成专门用于模仿某些文化、时期和地点的人工智能仍然可以提供信息,并可能为这些人如何相互交流提供更多的信息。特别是,带有智能程序的全息图能够学习并与真实的人接触,这对所有年龄段的学生来说都是一个有价值的学习工具。

Resurrected historical icons won’t give us honest answers to burning anthropological questions, but AI designed to mimic certain cultures, periods, and places can still be informative, and may shed more light into how these people interacted with one another. Especially, holograms with intelligent programs capable of learning and engaging with real people could be a valuable learning tool for students of all ages.

人或机器?

Man or Machine?

当然,尽管听起来很异想天开而且很令人兴奋,但这项技术并非没有公平的伦理问题。用人工智能重新创造失去的亲人的想法似乎很诱人,但它也开始模糊了不仅是生命和死亡之间的界限,而且是有意识和模仿之间的界限。随着用于创造这些人工复制品的技术的进步,将变得越来越难以区分模拟的人格和真实的人,在这一点上,我们必须考虑——它是一个人吗?它有权利吗?一旦被创造出来,人工永生者是否应该能够选择何时停用,来迎接第二次死亡?

Of course, as fantastical and potentially exciting as it sounds, this technology is not without its fair share of ethical concerns. The idea of recreating lost loved ones with an AI seems enticing, but it also begins to blur the line between not just life and death, but also sentience and imitation. As the technology used to create these artificial replicas advances, it will become increasingly difficult to distinguish simulated personality from a real person, at which point we must consider— is it a person? Does it have rights? Once created, should an artificial immortal be able to choose when it’s deactivated to die a second death?

如果这个想法能够以公正和公平的方式实施,明智地思考谁、何时、如何通过计算机人为地延长一个人的生命这件事才是真正必要的。我们的社会建立在压迫制度的基础上,并继续坚持这种制度,人工永生者可能会加强对某些群体的剥削;死人和计算机没有法律规定的权利。人工永生者可能有足够的智慧来执行任务和工作,而不被给予薪水,甚至他们可能会有足够的自我意识,让他们意识到他们正在被剥削,同时却没有自主权来控制自己或如何被使用。增强了类似人类个性的技术作为问题解决者、发明家和智能安全系统是非常有价值的,但真正的数字化人类仍然可能体验到情感,有抱负,并且他们作为我们社会的弱势成员,也应该得到公平的待遇。问题在于区分这两种情况——在什么时候机器会成为 "人"?计算机是否有可能不只复制意识,而是真正地保留意识?

Thinking wisely about who, when, and how we artificially extend a person’s life through a computer will be necessary if the idea can ever be implemented in a just and equitable way. Our society was built on and continues to uphold a system of oppression, and artificial immortals may contribute to the exploitation of certain groups; dead people and computers do not have rights enshrined in law. Artificial immortals may be intelligent enough to perform tasks and work jobs without being given compensation, may even be self-aware enough to know they’re being exploited while also having no autonomy or control over themselves and how they’re used. Technology augmented with human-like personalities could be invaluable as problem-solvers, inventors, and intelligent security systems, but real, digitized humans may still experience emotions, have aspirations, and deserve fair treatment as vulnerable members of our society. The problem lies in distinguishing the two— at what point does a machine become a “person”? Will it ever become possible for a computer to not only replicate, but actually, genuinely, preserve a consciousness?

由于创造人造版死者的技术可能很快就会实现,这些问题将变得更加重要。但不幸的是,现在他们还没有答案。像许多新的和未经探索的想法一样,它有能力提升、治愈和保存,但也有可能使压迫和不公正永久化。因此,随着我们进入越来越多的数字时代——计算机变得越来越像人,人类把自己更多的东西放到计算机上——我们必须思考我们对"活着"的定义。而且,也许最重要的是,我们应该思考"永生"意味着什么,以及我们在追求永远存在的过程中可能会牺牲些什么。

As the technology to create artificial versions of the deceased will likely soon come into fruition, these questions will become all the more important. And, unfortunately, for now they have no answers. Like many new and unexplored ideas, it has the ability to both uplift, heal, and preserve, but also to potentially perpetuate oppression and injustice. Therefore, as we move forward to the increasingly digital age— with computers becoming more humanlike and humans putting more of themselves into and on computers— it’s important to be conscious of what we define as “alive”. And, perhaps most importantly of all, we should consider what it means to be “immortal”, and what we risk sacrificing in the quest to exist forever.